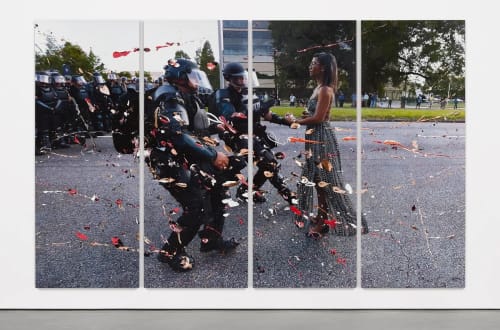

The source photograph — by Reuters photographer Jonathan Bachman, of Black Lives Matter protester Ieshia Evans standing off against police in Baton Rouge, La., during a protest of the killing of Alton Sterling by police in 2016 — is already a capturing of opposites. The kinetic poses of the police, clearly in motion, versus Evans’s stillness. The heaviness of the officers’ body armor versus the light billowing of the hem of Evans’s dress. Marc Quinn’s treatment of the image, made in 2017, takes it all a step further. Cutting the image into quarters accentuates what’s going on, and hearkens back to triptychs and other more antiquated forms of history paintings. The streaks of paint thrown across the painting add to the immediacy of the action, but also call attention to the change in medium, from photography to painting. What does it mean to try to immortalize an image? Which is another way of asking: how do we remember history?

Ieshia Evans is part of “History Painting +,” a short, sharp special exhibition of the work of artist Marc Quinn, running at the Yale Center of British Art on Chapel Street now through Oct. 16.

In this series of paintings, the artist states that he “reflects on contemporary history, its relationship to the media and to our greatest hopes and fears. The paintings … use one of the oldest forms of art — the history painting — and bring it into the present day. The series uses recent images of global conflict taken directly from the media, enlarged and painted with oil.… Individuals are focused on and singled out and although the works comment on the all-pervasive and intrusive nature of our media, they are also intimate portraits of people actively caught up in history. The works reflect on our digitized, globalized world; focusing on how collective memory can create our historical past.”

The painting of Evans is as good a starting point for the exhibit as any. Ieshia Evans, “a nurse from Pennsylvania,” an accompanying note relates, “joined the protests in Baton Rouge after seeing a video of the killing of Alton Sterling, a thirty-seven-year-old Black man shot at point-blank range while pinned to the ground by two police officers. Although Sterling’s family eventually was awarded a settlement for a wrongful death suit in February 2021, the officers were not charged.”

Bachman’s photograph was taken just before the police arrested Evans. His image circled the globe; The Guardian called it “a symbol of the civil unrest that has spread across the nation.” Evans spent a day in jail for her trouble, initially unaware of the effect the image of her was having. But two years later — a year after Quinn made his painting — she had a chance to reflect on the difference between the image and the reality in an interview with Huffington Post.

“I’ve had people who see the picture, and they have this idea in their head of who they want me to be,” she said. “And when they get a glimpse of who I actually am, they don’t like it.” In her seeming tranquility, many saw in her a validation of nonviolent protest. But she was more outspoken than that, in an article in the Guardian a month after her arrest. “I’m not against protesting peacefully, and I’m not pro-violence, but I’m definitely in favor of defending yourself. When people hear the way I speak, they’re usually like, ‘uhh, this is not what I thought. We thought you were just about peace and holding hands!’” she said.

“I think I will be remembered as a peaceful protester who saw injustice going on and took a stand,” she added. “I’d like to be remembered as a revolutionary.”

Quinn’s painting dives into that difficulty. There’s no doubt as to where his sympathies lie — with the underdog, with protests that emerge from the ground up, with moments of history in which regular people get a chance to have their say. But the severing of the image into four panels, and the paint splotched across it, also suggests something about the fraught way that we remember things, which is also about how we forget them. We remember things wrong. We get only a piece of the more complicated whole. We label things, put them in boxes, reduce them to bland symbols, and lose so much in the process. And the way we consume media now has only encouraged us to engage in that dynamic more quickly. Even if our sympathies are with the oppressed, even if we’re attuned to power and politics and history, what damage do we do when we remember so imperfectly, and forget so much?

MARC QUINN History Painting (Kiev [Kyiv], 22 January 2014).

As Quinn writes, “historic events quite obviously influence what is being reported in the news. But the big question of our age is: How do the images of the news media affect the course of events? What happens when images of anarchy and revolution, that we are constantly bombarded with, have colonized our minds? When they influence the way we think about places we have never been to, or about people we have never met?”

Quinn addresses his questions to paintings of London riots and Parkland shooting activists. It perhaps becomes most acute in a triptych of a riot in Ukraine in 2014. “This painting captures protests that erupted after Ukraine’s then-president Viktor Yanukovych reneged on an agreement with the European Union and pursued closer ties to Russia. The photograph on which the painting is based — taken by Vasily Maximov after new anti-protest laws came into effect — memorializes a day marked by violent police action against civilians,” an accompanying note explains. “In Quinn’s triptych, each panel presents a distinct moment within an overall narrative of Ukrainian resistance. At left, a protester is poised to hurl an object over the burning barricade. A second protester, in the center, throws a Molotov cocktail. To the right, an intact staircase presents a powerful symbol of the city’s sovereign fabric. The skeins of paint across the image echo the throwing motions of the figures, heightening the intensity and urgency of their actions. With Russia’s aggression against Ukraine coming full circle in 2022, this modern history painting presents not only a scene of chaos but also an image of individual and collective agency.”

But how well do we Americans understand what’s happening in Ukraine? How well do we grasp the history that led to the current conflict? What do we do with how quickly Zelensky acquired the trappings, in the U.S. popular imagination, of a folk hero — even as he remains a living, breathing human being trying to lead and preserve his country through an armed conflict against a foreign aggressor?

Quinn’s questions acquire a particular edge in the way they’re hung in the museum, not isolated in their own room, but interspersed among the museum’s permanent collection of history paintings across the centuries. In one way, Quinn’s paintings are a democratizing challenge to the more aristocratic works around them. In another, however, they are a challenge to viewers, to look behind and through any images, to see the politics around their creation, and to appreciate how much has been been forgotten within and especially beyond the image’s borders. We so often want a story simple enough to wrap our heads around in an instant, but understanding people for who they are, and why they do what they do, takes much longer than that.

Marc Quinn: History Painting +” runs at the Yale Center for British Art, 1080 Chapel St., through Oct. 16. Admission is free. Visit the museum’s website for hours and more details.